PRESTIDIGITATIONS

Pedro Lapa

At the beginning of the twentieth century the cinema of Méliès introduced the imaginary as the main pivotal dimension of the cinematographic language, thus replacing the naturalist dominance which guided the work of the Lumière brothers. In relation to the reporting of scenes from daily life, recorded by a still camera and which was as objective as technology allowed, there followed a rupture which developed the fantastic possibilities of a new language and which brought the cinema towards its spectacular and theatrical dimension. The possibilities of a new technology, although this might be using a theatrical rhetoric subordinated to the theatrical staging, was exploited in order to produce a specific imaginary. The artefact was not yet conditioned to the blinking of the eye which habit always supposes, that is, to its codifying within a system, thus generating a rhetorical device. This was the breaking in of the uncanny which brought with it the superimposing of another dimension of reality, purely imaginary, but which was nearest to it within the more objective form that photographic and cinematographic reality meant at that time. The trick, the effect, the artefact or the diversity of technical aspects which would later make up the cinematographic language, were the appearing of another approach to the real, which, within its

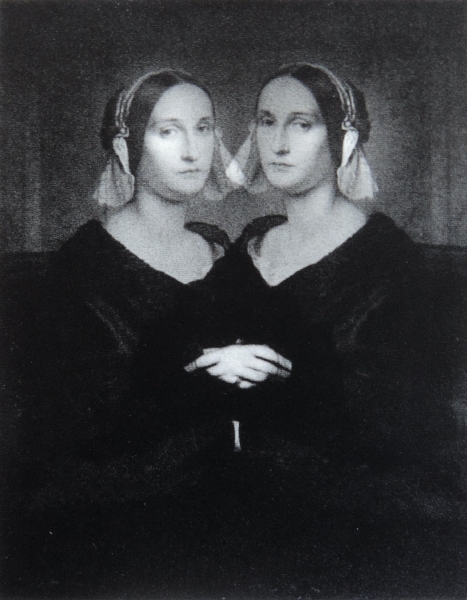

objectivity, revealed its simultaneous familiarity and uncanny as a fantasmatical dimension.It is particularly this aspect which the photo-montages of Susanne Themlitz isolate and reinscribe within another time - ours - thus opening the way for a critical revision which, on the one hand, returns a distance - the filmography by of Méliès - to its original context - which allows a direct articulation with its antecedents, such as the case of the symbolism of Gustave Moreau or of Odillon Redon; on the other hand, it approaches the surrealist collage of the objective chance. All of these different historical realities, to which the re-reading of Méliès work allows an approach through these photomontages, are not limited to an indifference generated by a mechanism or rhetorical device, but is above all the possibility of circumscribing the appearing of the uncanny within a certain context. The contingency of an unnameable particularity, which holds out against its very interpretation is superimposed by the witnessing character of photography which may be set within the diverse symbolic systems of aesthetics towards history. The uncanny which Freud analysed in Das Unheimliche, comes from a traumatic dimension with a compulsion for repetition and which is not able to be symbolised. This is not the case of its tragic aspect, as in Hoffmann’s Man of Sand, or even disturbing, as in many other works by the artist. Its uncanny might be, as happens with our observations in many similar situations in the many films by Méliès, that of the purely humorous and particularly irrational domain. The continuous game with the titles which these images carry out only serves to reinforce this aspect. Their humour defines the encounter with a real which cannot be symbolised. It paroxystically conjugates within it the order of the purely chance event with the notion of the determined cause, which itself is inherent to photography as a witnessing demonstration of the real. Accident and chance are thus a part of a much vaster universe of the forms of causality. Chance and determination coexist in the appearing of the fragments which come together and break with the naturalist order of the images. These are the metonymy of an absent universe which suddenly, and through the appearing of a fragment, becomes familiarly close to the statement. In this sense, the fantasmatical is not only the fragment which appears, but also the whole context becomes it, through a complicity which is not shown but is felt. The appearing of these fragments, due to the fact that they conjugate a random and causal order, inscribes a spectacular nature which is not restricted to the transcendence of the pure and simple breaking out of the imaginary, but which is simultaneously that of its double and of its interpellant threat. Jean-Luc Godard said that "there is no other way to explain how cinema, being the heir to photography, has always tried to be more real than life. And this is the way in which it once again becomes a spectacle’. It is of little importance that these fragments of images which appear are contiguous or connected to the respective setting, as they are enrolled within them through a desiring dimension, and as the principle of the sabotaging of the real. They are not the punctum which Roland Barthes speaks of, and which carries death and de-realisation through a mechanism of compulsion towards repetition, able to re-activate a ghost from the repressed subconscious and which radically questions all order, but they are close to the "objective chance event" of the surrealists. The appearing is here that of the revealing of another meaning than that which is stated on a surface and set up by the surroundings. It is the projection of desire onto an object or image which strangely reveal something which goes beyond the decipherable, beyond the artist's will or any reading. Thus the pastiche or similarity in relation to any symbolising aesthetics are purely parodical and the basis of the latter is clearly connected to a desiring and irrational order. The revealing of this excess sets up analogy and poetic reality as the order and disorder of these photomontages. Desire as a substance becomes the producer of the real and of the language itself. The supposed insinuated allegories, as well as the paraphernalia of the neo-classical rhetoric of the image, become laughable when they are revealed in this way.

In this sense, Méliès tradition, which was opposed to the documentary work of the Lumière brothers, is critically re-located within a different historical context, in which documentary work is once again affirmed as a practice appropriated from the plastic arts. From which may be repressed or submerged, in a somewhat puritanical manner, desiring raw material, as it appears that the set of these works wishes to show us.